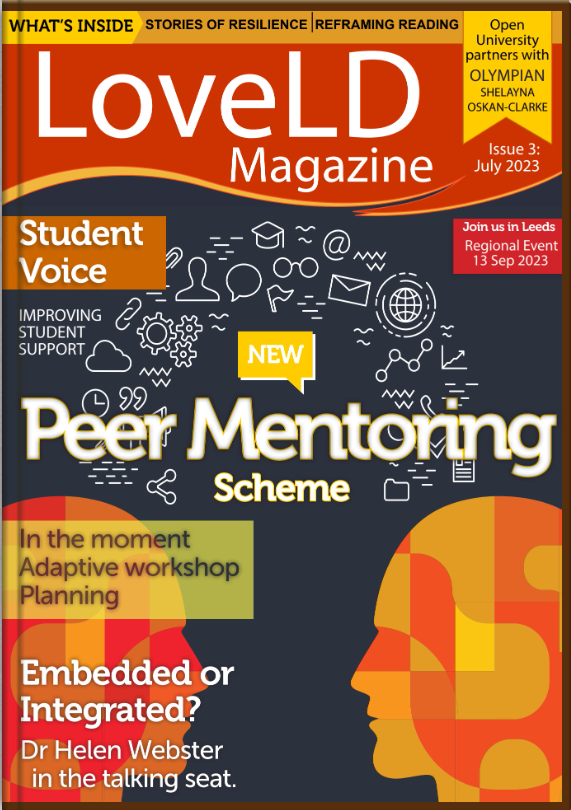

This post was written as an article for ALDinHE’s LoveLD magazine (Issue 3 July 2023), and is reposted here with permission. Go have a look at the magazine- there’s lots more good stuff there!

(many thanks to Katherine Jewitt who has done an amazing job of editing and typesetting the article, but I also wanted to illustrate this version with this terrifically flattering portrait captured at the same time as one of the photos used, by Jacqui Bartram!)

Embedded practice has long been the gold standard for Learning Development. Despite polemic arguments that study skills centres should be done away with as generic, bolt-on and ineffectual, any Learning Development service’s premium offer is the provision which is embedded in the discipline. With our foundations in Academic Literacies theory, which stresses the situatedness of learning, and our roots in EAP (amongst other fields), with its signature genre pedagogies, Learning Developers have pushed hard and negotiated carefully over many years to move away from one size fits all ‘bolt-on’ provision and towards more contextualised, tailored and differentiated ways of working. Our presence can be found in programme inductions and within modules and, where we’ve managed to build good relationships and trust, we are even called in to advise or collaborate on curriculum issues such as assessment design or academic integrity policy. We often still run central, generic provision in the form of workshops and online resources, but this is perhaps more a pragmatic concession to resourcing constraints than a pedagogic choice, to ensure that students on courses for which we’ve not had the leverage, staff or time to embed provision can still access the benefits of Learning Development. Our embedded work may not often be visible in our external facing online presence and can be overlooked from the outside, but over the years we’ve achieved much in advocating for and establishing embedded Learning Development provision.

What does embedded provision mean, though? At the very least, it is offered to students on a particular programme of studies, usually those at a specific stage of study such as first year undergraduates, finalists or taught Masters. The topic is determined by and negotiated with an academic member of staff such as a module leader, and may be regarding the skills they want their students to develop in that module, or in response to an issue arising in assessment or student engagement; many embedded sessions began as one-off reactive problem-solving interventions but their effectiveness soon led to them becoming a standard part of the timetable. As far as possible, session materials and guidance are tailored to the conventions of the discipline, its characteristic ways of thinking, practising and articulating learning, possibly connected to a specific assessment or transition point such as a first assignment, or newly encountered genre such as a dissertation. Sessions may be additional to the subject content teaching, or preferably scheduled as a standard part of the regular timetable so that students see their relevance and importance. With a well-timed and well-tailored Learning Development workshop, students are better able to make sense of and implement guidance in the context of the learning they’re currently engaged in.

Although highly prized in theory, in practice, the embedded session can be difficult and, in some cases, unrewarding to deliver, and I’ve reflected previously on my blog about why this might be. Of course, an embedded approach is of its nature more complex to achieve, and we have to work harder to get buy-in from our academic colleagues and do the work of tailoring our provision to each context (no small consideration given the small size of many of our teams!). Other difficulties are down to the compromises you need to make in practice – nothing’s perfect after all. Perhaps there wasn’t enough of a steer from your academic colleague, or you didn’t get the exemplars or assignment information you needed to really tailor your session, maybe the timetabled slot that would have made most pedagogic sense wasn’t possible, it could be that a huge cohort makes a really interactive approach tricky – these things happen. After all, the trump card we play – “we’ll come in and do it for you” – both buys us easier access to embedded opportunities, but also disincentivises any further engagement from our academic colleagues (Mrs Mopp will appear and do her magic, whatever it is…). There are also the innate challenges of trying to practise with a Learning Development pedagogy within a module which uses a different and possibly clashing approach to teaching, where the students don’t know you, aren’t used to the way you’re encouraging them to learn, and there’s no time to build that relationship and trust. Sometimes all this makes a session feel not so much embedded as ‘wheeled in’ – we have proximity to the curriculum with a timetabled slot for a specific programme, maybe a bit of superficial tailoring with the kinds of examples which reference the discipline, but beyond that, to what extent is it really embedded? Sometimes, for all our best efforts, it’s really just generic provision in a subject-specific guise. And sometimes, as much as we try to embed, even under favourable circumstances, it just still doesn’t feel like it’s satisfactory.

I wonder though, if we might do better to flip our perspective on embedded provision. The word ‘embedded’ has overtones of something being inserted into the curriculum which isn’t otherwise there, and which remains distinct from its surroundings. There is much reference in our institutions’ strategic documents and educational scholarship to employability, sustainability or wellbeing being embedded into the curriculum, but I’m not actually sure that academic skills is actually of the same order of things as those concepts. An Academic Literacies approach encourages us to move beyond a ‘study skills’ mindset that what we’re teaching are atomised, technical transferable skills and towards one which acknowledges the situated, contextualised, contingent and dynamic nature of these practices and discourses. Following this, we need to acknowledge that academic skills are not some Platonic ideal, existing in and of themselves as an objective, eternal, immutable truth. They are not a ‘must-have’ that we need to ‘equip’ or ‘provide’ students with, as if they were a Jane Austen heroine needing to acquire drawing, music and exam technique as standard ‘accomplishments suitable for a young lady’. Students only need study skills because of the curriculum: what they are learning and how. Academic skills do not exist separately from the curriculum, the curriculum gives rise to and shapes them. They emerge from it. They are constructed by its socially and pedagogically situated demands. How can we embed academic skills into the curriculum when they were already there?

The issue, of course, is not that academic skills need to be embedded into the curriculum, but that they are tacit, implicit, contested, part of the hidden curriculum. Seen this way, it is the role of Learning Developers to help make them visible and tangible, not by delivering or ‘giving’ students academic skills, but by helping students identify, interpret and negotiate the demands that their curriculum is giving rise to in ‘real time’, both in its disciplinary and institutional context, and also in the context of the student themselves. How is this student going to engage with that curriculum at this stage of their progression in that institution? Seen in this way, ‘academic skills provision’ isn’t fighting for space with subject content in a packed curriculum; you can teach the skills through the medium of the subject and the subject through the medium of the skills it requires, not at each others’ expense, as they are not entirely disparate things. From that perspective, I’m not sure that ‘embedded’ provision is the right word. Integrated, perhaps?

To integrate. To combine two or more things into a unified, more effectively functioning whole. What do we integrate? As intermediaries, we integrate the perspectives and aims of the student and the academic, the curriculum as it is designed and as it is experienced. We integrate the students’ past and present experience, personal circumstances, feelings, beliefs and knowledge about learning, techniques and strategies and individual study preferences into a unified approach to learning over which they have more agency. We integrate the hidden curriculum of academic skills and its associated cultural capital back into the curriculum as a whole. In terms of our provision, it is integrative, bringing together a diverse, inclusive and non-prescriptive range of guidance to accommodate each individual student, a multitude of different professional skills and techniques to suit different forms of teaching, and a constellation of complementary development opportunities from one-to-one, online, central workshops with embedded provision into a service which offers different approaches to suit different students. And in terms of embedded provision, we might seek to be integrated into the teaching team which designs and delivers the curriculum.

Embedded, integrated…. What practical difference would it make to our work, which term we use? For starters, the word ‘embedded’ is not student-centred in its perspective. If academic skills are already implicitly in the curriculum (because they are the curriculum, even if ‘hidden’ and not explicitly taught), then what’s really being embedded is us. We are the thing that wasn’t there that is being inserted. From our perspective, we’ve been embedded and gained access to the timetable, but from the students’ perspective, our presence may still feel rather incongruous (the term ‘embedded’ can also refer to a journalist attached to a military unit in a war – standing apart, and quite possibly standing out like a sore thumb!). If we think about integrated, rather than embedded provision, then what we’re aiming for is to be perceived as – indeed to be – a more integral part of the teaching team for students. Too often, our engagement with the curriculum is superficial and we might ourselves feel a bit ‘tacked on’. We might have access to subject specific exemplars and perhaps details of an assignment that our provision has been hooked onto, but beyond that, students are aware that we don’t know much more than that about the context for which we are preparing them, how these skills will play out across the whole programme, how expectations might change as they progress or take different modules, or how these skills are assessed in real terms. If we’re really going to support students’ academic skills development in context, we need to get our hands deeper into the curriculum.

This would of course change the nature of our conversation with our academic colleagues. Thinking of ourselves as integrated rather than embedded, we would need to work more systematically at programme level and with course teams rather than the more ad hoc piecemeal invitations from module leaders or individual lecturers, to look at how our input might be best deployed. We’d need to develop a clear framework to have the kind of in-depth conversations that would help us map out how and when academic skills arise throughout the course in their various contexts, consider how they play out with input from staff and student feedback, and, crucially, scope out opportunities where skills development can be introduced, scaffolded and built on in conjunction with the assignments or transition points that give rise to them. This might mean being more actively involved in course and module development and review as a regular part of these processes to offer an academic skills development lens – a more top down approach to complement the bottom up approach that Learning Development initially adopted as it found its feet as a profession. In some isolated instances, we have managed to gain this level of access, but rarely in an established capacity across the board. This approach is more time consuming and resource intensive, but equally might give us a sounder basis to demonstrate our impact and make the case for more resourcing, as well as give us better feedback loops to work with teaching teams as well as students. The perspective we gain from our intermediary role, especially in one to one work, gives us privileged access into how students are experiencing their learning, which would be an enormously valuable contribution to any teaching and learning design process. This in turn makes for a less deficit approach as we can also meaningfully address academic skills issues in the curriculum, rather than locating ‘the problem’ only in students and expecting all the accommodation to be on their side.

Thinking of our provision as integrated might also help us to enhance those aspects of embedded provision that we know are less satisfactory. Depending on resourcing and how our provision is used by academic colleagues, we are often constrained to one-shot sessions, which, especially in more ‘study skills’ framed provision in first year undergraduate courses, is intended to ‘do the job’ for the entirety of the student’s degree, and is simply expected to carry too much. If we take an Academic Literacies approach to the situatedness of learning, or indeed just look at the curriculum over the whole programme, expectations of student learning evolve, the bar is raised and contexts vary. If a final year student is still writing essays the same way as they were taught in their first term of their first year, they will find that their marks start to dip, as the unspoken expectation is that they will have developed further since then and marking criteria will reflect a higher level. Yet very often we speak of study skills as an immutable transferable entity that once you have acquired, you then possess, instead of dynamic, evolving and situated practices. I’m not sure I would say I ‘have’ the skill of academic writing, for example – I’m still learning and developing how to write in new contexts! I don’t (or I try not to) teach criticality to first years in the same way I would to final year dissertation students, or reading and note-taking to students facing exams as I would those approaching a dissertation, as the requirements are different. We know in theory that this is the case, but in practice, we also know that we have one session with the first years on academic writing, or whichever topic, and we need to cram as much in as will see them through as long as possible. What’s useful and relevant to students at the beginning of a degree or dissertation process isn’t what’s useful and relevant towards the end, but we may have only one hour to cover it all. This means in effect that students are overloaded with advice which isn’t necessarily immediately relevant or applicable, ‘just in case’, ‘for later’, and our embedded provision starts to become generic and ‘wheeled in’. We’re not ‘working alongside’ students in real time but in the abstract. They have to trust us, not their own experience, for what they need.

An integrated, emergent approach, however, might look at differentiating provision for each level of transition within a student’s learning journey and base provision on what’s arising from the curriculum at that stage, at the most timely point. We know the ‘second year slump’ is a thing, and we know that this is where they need to review and renew their practices, but students may reject another embedded skills session at this stage as ‘we’ve already done that last year’. If Learning Development is integrated into their curriculum though, in multiple complementary ways, we can consider models such as the true student-led experiential workshop, learning in the moment from questions that are currently concerning them, rather than delivering slightly paternalistic guidance with hypothetical activities not rooted in their current reality. It could be a process of spiral learning, iterating and building on previous provision in ways that reinforce their learning and evolve it to the appropriate level for that stage. Some provision might be more obvious, like an LD workshop, other aspects might be lighter touch- a ten minute activity at the start of a lecture, a talking point as part of a seminar, a reflective account shared with a peer or a coaching discussion with a personal tutor, joined up as a deliberately aligned constellation of academic skills provision. This is more likely to land well with students than a Learning Developer trying to convince them in a one-shot session that this stuff will come in useful later, by which time it will have been forgotten, as it didn’t make sense or seem relevant.

This is labour-intensive of course, and would require a huge Learning Development team (no harm in dreaming!). But taking an integrated perspective, we could look at collaborating with our academic colleagues to design what integrating academic skills might look like, and then look at who is best placed to offer what. I’d feel that there was much less at stake for my integrated workshop if I knew that their academic lecturer and I had co-created small activities to prepare the ground, and that following our session, there would be further co-designed opportunities to reflect on and extend what we’d discussed, perhaps with peer mentors or personal tutors, all constructively aligned. And of course I wouldn’t need to anticipate what students would need in later stages, as I’d know that there would be appropriate provision offered then, and my provision wasn’t once and for all. We might feel under less pressure then for that one-shot workshop to deliver everything a student might need, as we’d know the wider context in which it sits, and the other elements which support it. Our provision would be integrated not just with the timetable and the discipline, as in embedded practice, but with the curriculum itself, and with the wider teaching team.

We could then really capitalise on what a Learning Developer might be best placed to do within the curriculum, as someone who can offer a safe, non-judgemental, emancipatory space outside of subject knowledge and assessment, able to help uncover the hidden curriculum of academic skills, and what the subject lecturer is best placed to provide, as the one who is the subject expert and the authority on the assessment process but whose unconscious competence might not allow them to stand outside their own discipline to see its norms clearly, and whose role in assessment does not allow for a non-judgemental space. In this form of provision, we’d be working as an interprofessional, integrated team with a clearly defined, interdependent role for each. The more this requires us to clearly articulate and delineate our expertise and role, the better it will be for the profession more generally in terms of how we are understood and valued – Mrs Mopp’s magic is real, but is a spell worked best in partnership rather than cast alone with borrowed ingredients. And as intermediaries, we can also work with staff in a consultative capacity more akin to our educational development colleagues, to help them map out and articulate their academic skills expectations, and review their curricula where needed.

This isn’t to argue that there’s no space for centralised provision – done well, central ‘subject and stage agnostic’ central workshop programmes might be better placed than integrated provision to help students share practice and raise awkward questions with a group which is not their immediate peers. The mixed group workshop can deliberately juxtapose the differences between subjects to make the disciplinary norms stand out more strongly, and smaller numbers can permit a more genuinely workshop format than the large scale teaching we often do within programmes. Online academic skills resources can often be woefully deficit and generic, but in an integrated model, using a programme’s VLE to good effect, might play a more deliberate and tailored role as one of the complementarily designed facets of integrated provision. And I will always argue for the central place of one to one provision in Learning Development. Done skillfully, one to one tutorials offer the purest form of Learning Development, a liminal third space which is entirely tailored to the needs of that student, standing outside of the judgement inherent in assessment and above the specificities of subject knowledge so the student can focus on reflecting on their own learning. Alongside curriculum-integrated provision, the one to one tutorial is an alternative space where the student can develop in their own time rather than the timeline set by the curriculum, as for many reasons, the two may not align. And of course, one to ones are the lifeblood of Learning Development expertise, the source of our perspective of the students’ own lived experience of the curriculum, and what distinguishes us from our Educational Development colleagues. But in an integrative Learning Development model, the different aspects of our provision might be free to play the role they are best suited for, rather than each being seen as mopping up what the others aren’t resourced or positioned to achieve.

We’d need to work hard for this model, especially if it’s to become part of the teaching and learning processes and structures across an institution, and we’re a long way off yet. There’s still plenty of progress to be made regarding an embedded model, but perhaps for now we can look beyond embedding as the pinnacle of Learning Development provision, to the next and more ambitious phase of our evolution, as integrated provision.